| 拉休里龍屬 化石时期:白堊紀晚期

| |

|---|---|

| |

| 復原圖 | |

| 科学分类 | |

| 界: | 动物界 Animalia |

| 门: | 脊索动物门 Chordata |

| 纲: | 蜥形纲 Sauropsida |

| 总目: | 恐龍總目 Dinosauria |

| 目: | 蜥臀目 Saurischia |

| 亚目: | 獸腳亞目 Theropoda |

| 科: | †阿贝力龙科 Abelisauridae |

| 亚科: | †玛君龙亚科 Majungasaurinae |

| 属: | †拉休里龍屬 Rahiolisaurus Novas et al., 2010 |

| 模式種 | |

| †古吉拉特拉休里龍 Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis Novas et al., 2010

| |

拉休里龍(屬名:Rahiolisaurus,意為「來自Rahioli村的蜥蜴」)是一屬阿貝力龍科的獸腳亞目恐龍,生存於白堊紀晚期的印度。化石來自至少7個不同個體,分別代表不同生長階段,但都屬於單一物種,是在古吉拉特邦的拉米塔組所發現,地質年代為馬斯垂克階,約7210萬至6600萬年前,使牠成為已知化石紀錄中最後的非鳥類恐龍之一。模式種古吉拉特拉休里龍(Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis)於2010年被發表敘述。

發現及命名

於1995年和1997年的兩次考察期間,在一個50平方公尺的採石場中發現了數個阿貝力龍科遺骸,採集到的部位包括頸椎、胸椎、薦椎及尾椎、部分胸帶和骨盆、還有許多後肢骨。因為挖出了七個不同尺寸的脛骨,代表這個化石群由七個不同發育階段的個體組成。有些重複的骨骼如髂骨、恥骨、股骨、脛骨表現出相似於典型阿貝力龍科的特徵。雖然個體間的不同尺寸代表成長差異,卻幾乎沒有發現任何分類學上的差異。因此在費爾南多·諾瓦斯等人(2010)的描述中,整個採石場的獸腳類群集都屬於單一物種拉休里龍。[1]

新發現的阿貝力龍科骨骼被個別編號:正模標本是個部分連接的骨盆及股骨,包含一個右髂骨(ISIR 550)、一個右恥骨(ISIR 554)、一個右股骨(ISIR 557)。此外,一個樞椎(ISIR 658)被發現與第三(ISIR 659)、第四(ISIR 660)頸椎關節連接在一起。標本現保存於加爾各答印度統計研究所的地質博物館。[1]

拉休里龍的屬名是以發現地附近的拉休里村(Rahioli)命名;種名意指來自古吉拉特邦。[1]

敘述

拉休里龍最初被描述為一種大型阿貝力龍科,身長約8公尺。[1]但這項估計依據的ISIR 557標本後來被估計長6.3公尺。[2]2016年莫里納-培雷茲和拉臘門迪估計ISIR 436標本身長9.3公尺及體重2噸。[3]牠與另一種印度阿貝力龍科勝王龍有許多相似之處,但也有一些不同點,例如整體較纖細、修長的後肢。[1]如同典型的阿貝力龍科,拉休里龍有四根手指和非常短的手臂,並以結構沉重的頭部作為補償的掠食工具。頭骨和牙齒都短,可能有中等強度的下頜肌肉。[4]依照阿貝力龍科,拉休里龍可能與異特龍有相近的咬合力約3,500牛頓(790英磅力)。[5]

分類

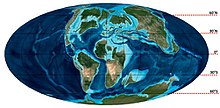

2014年古生物學家Thierry Tortosa建立了瑪君龍亞科,依照一些生理特徵上的差異,例如:加長的眶前孔、矢狀嵴像頭部前方擴張為三角形面,以將歐洲新發現的阿克獵龍、瑪君龍、印度龍及勝王龍與南美洲阿貝力龍科區別開來。雖然海洋造成巨大的隔閡,有認為在白堊紀晚期,歐洲、非洲、馬達加斯加和印度間發生了阿貝力龍科的遷徙,最後使南美洲的阿貝力龍科孤立在外;遷徙可能發生在非洲,因為歐洲和印度都離這很近,火山島弧Dras-Kohistan可能允許了跳島遷徙的可能性,並提供通往亞洲的間接路徑;但這樣的解釋仍充滿爭議。[6][7]

以下演化樹取自Tortosa(2014):[6]

| 角鼻龍下目 Ceratosauria |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

古生態學

拉休里龍發現於拉米塔組,放射性定年法測量地層年代為白堊紀最末期的馬斯垂克階。當時此地景觀呈現乾旱或半乾旱氣候,有條河流經過可能提供了周邊灌木叢的水分,這是德干暗色岩火山爆發時所形成的。[8][9]拉休里龍可能棲息在相當於現在的訥爾默達河谷地區。該地層以蜥腳類蛋巢遺址而聞名,產出許多種恐龍蛋,蜥腳類可能會選擇沙質土來產卵;[10]雖然也發現了大型獸腳類的蛋,不確定是否屬於拉休里龍。[11]蜥腳類糞化石表示牠們棲息於森林環境,食用羅漢松、南洋杉、松柏門的掌鱗杉科、蘇鐵、棕櫚樹、早期的草、石竹、無患子、爵床等開花植物。[12]

拉米塔組有許多已敘述恐龍:西北阿根廷龍科的福左輕鱷龍;阿貝力龍科的印度龍、印度鱷龍、拉米塔龍、勝王龍;泰坦巨龍類的耆那龍、泰坦巨龍、伊希斯龍。白堊紀印度的阿貝力龍科和泰坦巨龍類多樣化表示牠們與岡瓦納大陸其他地區的相似物種群集(及相似的棲息環境)有接近屬性。[13]印度恐龍可能於KT交界的大約前35萬年,因為火山活動而滅絕;儘管牠們可能會避開裂縫噴發口和熔岩流經地區。[14]

參見

參考來源

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Novas, Fernando E., Chatterjee, Sankar, Rudra, Dhiraj K., Datta, P.M. (2010). "Rahiolisaurus gujaratensis, n. gen. n. sp., A New Abelisaurid Theropod from the Late Cretaceous of India" in: Saswati Bandyopadhyay (ed.): New Aspects of Mesozoic Biodiversity. Springer Berlin / Heidelberg. pp. 45–62. doi:10.1007/978-3-642-10311-7. ISBN 978-3-642-10310-0.

- ^ Grillo, O. N.; Delcourt, R. Allometry and body length of abelisauroid theropods: Pycnonemosaurus nevesi is the new king. Cretaceous Research. 2016, 69: 71–89. doi:10.1016/j.cretres.2016.09.001.

- ^ Molina-Pérez & Larramendi. Récords y curiosidades de los dinosaurios Terópodos y otros dinosauromorfos. Barcelona, Spain: Larousse. 2016: 256. ISBN 9780565094973.

- ^ Paul, G. S. The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs. Princeton University Press. 2010: 84–86. ISBN 978-0-691-13720-9.

- ^ Delcourt, R. Ceratosaur Palaeobiology: New Insights on Evolution and Ecology of the Southern Rulers. Scientific Reports. 2018, 8 (9730). PMC 6021374

. PMID 29950661. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28154-x.

. PMID 29950661. doi:10.1038/s41598-018-28154-x.

- ^ 6.0 6.1 Tortosa, T.; Buffetaut, E.; Vialle, N.; Dutour, Y.; Turini, E.; Cheylan, G. A new abelisaurid dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous of southern France: Palaeobiogeographical implications. Annales de Paléontologie. 2014, 100: 63–86. doi:10.1016/j.annpal.2013.10.003.

- ^ Kapur, V. V.; Khosla, A. Late Cretaceous terrestrial biota from India with special reference to vertebrates and their implications for biogeographic connections. Cretaceous Period: Biotic Diversity and Biogeography. 2016, 71: 161–172.

- ^ Brookfield, M. E.; Sanhi, A. Palaeoenvironments of the Lameta beds (late Cretaceous) at Jabalpur, Madhya Pradesh, India: Soils and biotas of a semi-arid alluvial plain. Cretaceous Research. 1987, 8 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1016/0195-6671(87)90008-5.

- ^ Mohabey, D. M. Depositional environment of Lameta Formation (late Cretaceous) of Nand-Dongargaon inland basin, Maharashtra: the fossil and lithological evidences. Memoirs of the Geological Survey of India. 1996, 37: 1–36.

- ^ Tandon, S. K.; Sood, A.; Andrews, J. E.; Dennis, P. F. Palaeoenvironments of the dinosaur-bearing Lameta Beds (Maastrichtian), Narmada Valley, Central India. Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 1995, 117 (3–4): 153–184. doi:10.1016/0031-0182(94)00128-U.

- ^ Lovgren, S. New Dinosaur Species Found in India. National Geographic News. 13 August 2003 [8 April 2009]. (原始内容存档于2018-07-21).

- ^ Sonkusare, H.; Samant, B.; Mohabey, D. M. Microflora from Sauropod Coprolites and Associated Sedimentsof Late Cretaceous (Maastrichtian) Lameta Formation of Nand-Dongargaon Basin, Maharashtra. Geological Society of India. 2017, 89 (4): 391–397. doi:10.1007/s12594-017-0620-0.

- ^ Weishampel, D. B.; Barrett, P. M.; Coria, R.; Le Loeuff, J.; Xijin, Z.; Xing, X.; Sahni, A.; Gomani, E. M. P.; Noto, C. R. Dinosaur Distribution. Weishampel, D. B.; Dodson, P.; Osmólska, H. (编). The Dinosauria 2nd. Berkeley: University of California Press. 2004: 595. ISBN 978-0-520-24209-8.

- ^ Mohabey, D. M.; Samant, B. Deccan continental flood basalt eruption terminated Indian dinosaurs before the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary. Geological Society of India Special Publication. 2013, (1): 260–267.