| 1934年君士坦丁骚乱 | |

|---|---|

| |

| 位置 | |

| 日期 | 1934年8月3日—8月5日 |

| 目標 | 阿尔及利亚的犹太人[1] |

| 類型 | 骚乱[1]、纵火[2]、抢劫[3][4] |

| 死亡 | 25名犹太人、3名穆斯林[4][5] |

| 受傷 | 大约200人[4][5] |

| 動機 | 反犹太主义[6] |

1934年君士坦丁骚乱是法属阿尔及利亚君士坦丁市爆发的一场针对当地犹太人的骚乱[1][7][8],骚乱根源被认为是法国殖民政府区别对待阿尔及利亚的犹太人和穆斯林[4]。目前尚不清楚骚乱的确切原因,但各种说法认为骚乱是由君士坦丁西迪拉赫达尔清真寺内一名犹太男子与一些穆斯林之间的争吵引发的[4][9]。据多个消息来源报道,为期三天的骚乱造成25名犹太人和3名穆斯林死亡,多家犹太机构遭到洗劫[4][5]。这起骚乱事件也被描述为一场反犹骚乱[6]。

背景

1934年君士坦丁骚乱的背景可以归结为法属阿尔及利亚日益高涨的反犹太主义。紧张局势的一个根源是1870年10月实施的《克雷米厄法令》,该法令允许阿尔及利亚犹太人获得法国公民身份。[10][11]对于法国政府来说,这项法令被视为北非“文明使命”的一部分[12]。

法国多个政党和政治人物都反对这一决定,其中许多原因都源于反犹太主义或更普遍的仇外心理。法国人反对该法令的原因之一是他们认为犹太人更适合从事商业工作,他们担心法国公民身份会让更多的犹太人加入法国军队。许多右翼、激进的法国民族主义者同意查尔斯·杜布泽的说法,即阿尔及利亚犹太人与西方文明根本不相容。[11][5]前奥兰行政官兼驻阿尔及利亚特派专员杜布泽指出,阿尔及利亚犹太人的“道德、语言和服饰”使他们成为阿拉伯人,因此有别于法国人[5]。激进的法国民族主义者认为,阿尔及利亚犹太人逐渐在政治上融入并同化法国社会,对“本土”法国社会构成了威胁[5]。

20世纪初,阿尔及利亚的反犹太主义情绪高涨。例如,反犹太主义运动拉丁裔联盟的领导人朱尔斯·莫勒博士于1925年成为奥兰市长,并于1928年成为该市的议员。声称左翼政治提倡“犹太帝国主义”的加布里埃尔·兰伯特神父(Abbé Gabriel Lambert)于1934年成为奥兰市长。奥兰和君士坦丁的本地报纸《小奥兰报》和《论坛报》(La Tribune)定期传播反犹太主义信息。[5]

有证据表明,反犹太主义的法国定居者试图在阿尔及利亚穆斯林群体中灌输反犹太主义情绪,并引发君士坦丁的穆斯林和犹太人之间的争吵[13]。根据当时媒体和警方的报告,未找到证据表明本地穆斯林政客或神职人员在20世纪20年代和30年代公开宣传了反犹太主义信息[13]。人们还普遍认为是纳粹煽动了这场骚乱[6]。

过程

君士坦丁大屠杀的起因尚有争论。普遍的共识是,冲突的最初起因是1934年8月3日犹太人祖阿夫埃利亚侯·哈利法与穆斯林信徒在西迪拉赫达尔清真寺发生的争执。穆斯林称哈利法喝醉了,侮辱了伊斯兰教。犹太当局的一份报告称,哈利法没有喝醉,在与穆斯林发生争执后,穆斯林诅咒了哈利法的信仰,哈利法也诅咒了穆斯林和他们的信仰。[8][9]法国殖民当局只报道了穆斯林版本的事件,多数学者认为这引发了这场屠杀[14]。也有报道称,哈利法曾在清真寺的墙上小便,可能引发了骚乱[9]。8月3日晚,在哈利法的公寓发生的暴力示威活动中,一名穆斯林男子腹部中枪[4]。法国政府派出148名士兵和52名警察前往控制该市的骚乱[15]。

8月4日星期六,骚乱仍在继续,当地领导人、穆斯林和犹太社区代表同警方和军方代表聚集在一起,商讨和平结束暴力的对策。[4][15][3]

8月5日星期日,当地穆斯林政治人物穆罕默德·萨利赫·本德杰鲁遭暗杀的谣言四起,暴力事件再度爆发。然而,谣言最终被证实是假的。[4][16]骚乱持续了数小时,并蔓延至君士坦丁附近的城镇[4]。反对种族主义和反犹太主义国际联盟(LICRA)君士坦丁分部张贴了阿拉伯语和法语的海报,呼吁和平并结束暴力[17]。

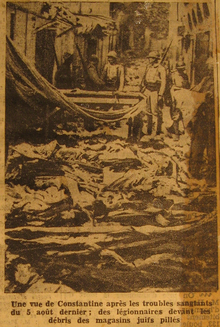

据报道,骚乱最终导致25名犹太人和3名穆斯林死亡,约200人受伤,多家犹太企业和住宅也遭到摧毁或抢劫。[4][5][3]

报道

犹太电讯社于1934年8月8日报道:

一位今天成功抵达这座城市的犹太电讯社记者描述了当时的情景:犹太女孩的乳房被割掉,儿童身上有多处刀伤,全家人被锁在家中被烧死,场面十分凄凉和恐怖。

“世人需要几天的时间才能真正了解阿拉伯人在犹太人大屠杀期间犯下的全部暴行”,记者在电报中写道。

“我能想到的唯一可与之相比的就是1929年的巴勒斯坦骚乱。我发现犹太女孩的乳房被割掉,灰胡子犹太人被刺死,犹太儿童死于多处刀伤,全家都被锁在家中,被暴徒活活烧死。”

“就像1929年的巴勒斯坦一样,死伤人数多达数百人,但官方没有给出确切数字。医院里挤满了犹太受害者,医院门口围满了半疯的妻子和母亲,她们想确定自己的亲人是否在死伤者之列,或者是否成功逃脱了屠杀。”[2]

后续

骚乱和屠杀之后,有法国媒体因刊登了残缺尸体的照片而受到批评,被认为煽动了有害的社区气氛。[18]

8月8日,受害者葬礼期间举行了纪念仪式。犹太社区领袖和殖民当局代表出席了仪式,穆斯林官员未前往现场。几天后,君士坦丁穆斯林当局发表了一份声明,呼吁拒绝暴力,并谴责任何在政治上利用反犹太主义骚乱的企图。[18]

相关条目

参考资料

- ^ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Sharon Vance. The Martyrdom of a Moroccan Jewish Saint. BRILL. 2011-05-10: 182. ISBN 978-90-04-20700-4 (英语).

Muslim anti Jewish riots in Constantine in 1934 when 34 Jews were killed

- ^ 2.0 2.1 Algeria Riots Checked. Jewish Telegraphic Agency. 1934-08-08 (英语).

- ^ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Boum, Aomar. Partners against Anti-Semitism: Muslims and Jews respond to Nazism in French North African colonies, 1936–1940. The Journal of North African Studies. 2014, 19 (4): 557. S2CID 144799112. doi:10.1080/13629387.2014.950175 (英语).

- ^ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 Cole, Joshua. Constantine before the riots of August 1934: civil status, anti-Semitism, and the politics of assimilation in interwar French Algeria. The Journal of North African Studies. 2012, 17 (5): 839–861. S2CID 143595241. doi:10.1080/13629387.2012.723432 (英语).

- ^ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 5.7 McDougall, James. A History of Algeria. Cambridge University Press. 2017: 116–117. ISBN 978-0-521-85164-0 (英语).

- ^ 6.0 6.1 6.2 The Constantine Pogroms. The Sentinel. 1934-08-23 [2024-07-12] (英语).

- ^ Stein, Rebecca. Palestine, Israel, and the Politics of Popular Culture. Duke University Press. 2005: 237. ISBN 0-8223-3504-2 (英语).

- ^ 8.0 8.1 Levy, Richard. Antisemitism: A Historical Encyclopedia of Prejudice and Persecution, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. 2005-05-24: 139 (英语).

Between August 3 and 5, 1934, Muslim mobs went on a rampage in the Algerian city of Constantine, attacking Jews and Jewish property. In the attack, 25 Jewish men, women, and children were killed, most from having their throats cut or their skulls crushed, and 26 more were injured, according to official statistics. More than 200 Jewish-owned stores were ransacked. The total property damage to homes, businesses, and synagogues was estimated at over 150 million Poincare francs. Some 3,000 people, one-quarter of Constantine's Jewish population, were in need of welfare assistance in the aftermath of the pogrom. During the rampage, anti-Jewish incidents were recorded in the countryside of the Department of Constantine, extending over a 100-kilometer radius. Jews were murdered in Hamma and Mila, and in Ain Beida, Jewish homes and businesses were looted. During much of the rioting, the French police and security forces stood by and did little or nothing to stop the rioters.

- ^ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Allali, Jean-Pierre; Musicant, Haim. Des Hommes Libres: des histoires extraordinaires de l'histoire de la LICRA. Editions Bibliophane. 1987: 22–23 (法语).

- ^ Stein, Sarah Abrevaya. Saharan Jews and the Fate of French Algeria. Chicago, IL: The University of Chicago Press. 2014: xi. ISBN 978-0-226-12374-5 (英语).

- ^ 11.0 11.1 Schreier, Joshua. Arabs of the Jewish Faith: The Civilizing Mission in Colonial Algeria. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. 2010: 8. ISBN 978-0-8135-4794-7 (英语).

- ^ McDougall, James. A History of Algeria. Cambridge University Press. 2017: 115. ISBN 978-0-521-85164-0 (英语).

- ^ 13.0 13.1 Cole, Joshua. Constantine before the riots of August 1934: Civil Status, Anti-Semitism, and the Politics of Assimilation in Interwar French Algeria. The Journal of North African Studies. 2012, 17 (5): 847. S2CID 143595241. doi:10.1080/13629387.2012.723432 (英语).

- ^ Samuel Kalman. The Extreme Right in Interwar France: The Faisceau and the Croix de Feu. Ashgate Publishing. 2008: 210–216 [2024-07-12] (英语).

- ^ 15.0 15.1 Cole, Joshua. Lethal Provocation: The Constantine Murders and the Politics of French Algeria. Cornell University Press. 2019: 123 (英语).

- ^ Cole, Joshua. Lethal Provocation: The Constantine Murders and the Politics of French Algeria. Cornell University Press. 2019: 130–131 (英语).

- ^ Cole, Joshua. Lethal Provocation: The Constantine Murders and the Politics of French Algeria. Cornell University Press. 2019: 126 (英语).

- ^ 18.0 18.1 Joshua Cole. Antisémitisme et situation coloniale pendant l'entre-deux-guerres en Algérie. 20 & 21. Revue d'histoire. 2010 [2024-07-12]. (原始内容存档于2017-12-23) (法语).